Tips and tricks for reversing foreign architecture games

TL;DR

Some common techniques used while reversing unknown architectures seen through the lens of an 80's game hacking challenge from 0CTF22If you’ve played enough CTF or lived long enough as a curious Computer Person, it’s likely you’ve run into a device/piece of software that is built on an architecture you’ve never reversed before. In this year’s edition of 0ctf, I encountered something similar, and I thought I’d make a little post about some common tricks I’ve used in these situations based on this challenge. As usual, I did this challenge with various people who stopped by in the Shellphish discord, but mostly a newer recruit to the team, @zammo.

The Challenge

In this challenge, we’re provided with only a single file called game.bin. The description for the challenge only says: “back to the 90s.”

Like any random file that you’re given, it’s best to see if file has any knowledge of it:

λ file game.bin

game.bin: Vectrex ROM image: "VECTOR_GAME\200"

Seeing as it does, our introduction begins with a completely foreign device and architecture.

The Vectrex Console

In times like these, it’s always best to start with Wikipedia–it tends to be a great source of general knowledge for tech people. The Vectrex page already tells us the most important thing: that the console’s circuit board, i.e., its architecture, is a Motorola 6809. I’ve heard other CTFers refer to this arch as m6809.

m6809, in this case, is an 8bit architecture that supports some 16bit operations, which means we will likely only ever be dealing with 1 byte at a time. Mixed 8 and 16 bit operations are like ARM Thumb Mode. The game we’re given is essentially a program (ROM) for this system which is full of m68k instructions wrapped by some assets and loading information.

Reversing Questions

Understanding the very basics of this program is essential, but it still leaves a lot of questions. These questions are usually the same questions I ask whenever reversing something not mainstream. Most of them are inspired by my mentor @fish.

- What tools did the author (and normal devs of the platform) use to make this program?

- If this is a program wrapped in something deeper, where is the entry point? How do emulators find the entry point?

- Do any revealing strings tell us more about the program’s origins?

- If the flag is not a hardcoded string, how are they hiding it?

We’ll attack these in order to get a better understanding of the program.

Tooling

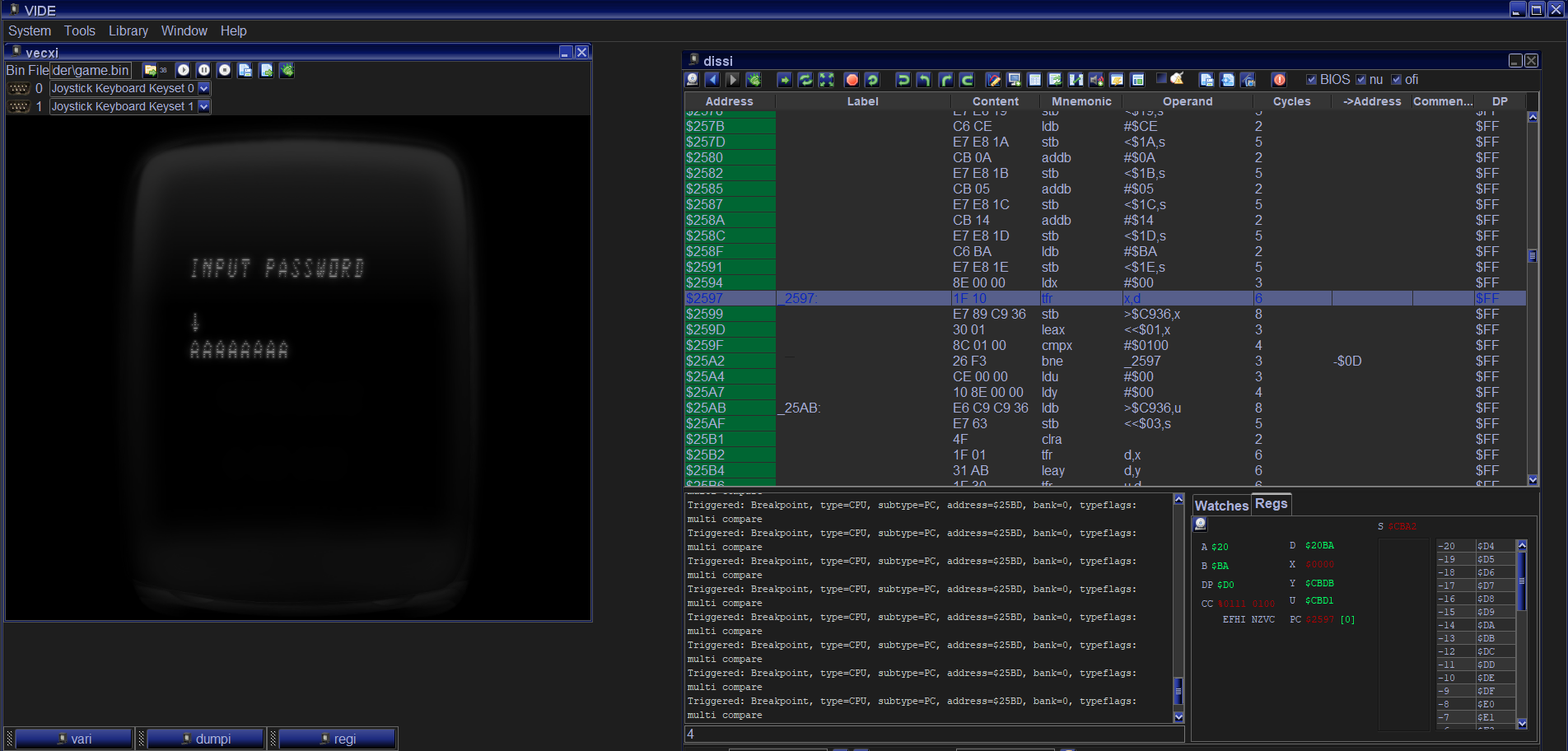

After some google searching with phrases like “vectrex debugger ide,” a blog by a somewhat active developer shows us what people use to develop in this platform: VIDE: Vecrex Integrated Development Environment. Blogs from active developers of one-offs like this are usually gold mines for finding information on how to understand this platform.

The “IDE” is somewhat archaic, but hey, it works!

The IDE allows us to step-debug, dump memory, and even modify memory and registers as it runs! It’s a full-on debugger that also gives us insight into what the disassembly looks like when correctly assembled. With this debugger and an m6809 reference sheet we found from googling, we are set! A reference sheet is needed when you don’t understand how an arch works.

During this scouting phase of tools, we also found a simple emulator called vecx, which was preferred because of how easy the code was to understand. The emulator even included an entire emulation implementation of m6809 in simple C. This was useful because it also allowed us to debug it quickly and find that the entry point of the program is 0x1e. You can reproduce this by setting a breakpoint in the very first read8 of the program. I’d say it’s always helpful to have a simple reference to see how other noobs approached the same problem.

With that squared away, we now understand how other people develop in this arch. The last part we need is some form of static analysis for this ROM. In most cases like this, there will not be some plugin readily available for your decompiler. At this point, you can decide whether to implement an entire loader, which unwraps the object and tells the decompiler where the code begins, or manually mark the code yourself. In another writeup of this same challenge, which is done spectacularly, the author invests his time in writing his own loader for Ghidra.

Static Analysis

When running the game, as shown in the IDE picture, it simply asks for a password. It’s eight chars, outside the bruteforceable range for a CTF. At this moment, we should be thinking about two more questions:

- Is verification time constant?

- Is each char verification dependent on the entire password?

Answer 1 is tricky because we can only debug this program once it is being emulated, which makes it extremely hard to detect changes in time when verifying something like AAAAAAAA and BAAAAAAA. Instead, we keep ##2 in mind.

We will be using IDA for static analysis, but you should be able to do this in Ghidra or Binja. For IDA, we need to manually mark the start of the code section because IDA has no knowledge of this binary format; however, it does understand m6809 instructions. In IDA, going to the EP we discovered earlier, 0x1e, typing C while over it, we get disassembled instructions with general function boundary guesses from IDA.

We are left with the following functions:

sub_974

sub_A5F

sub_1470

sub_14D7

sub_1A63

sub_1C60

sub_219F

sub_2549

sub_2851

sub_2D26

sub_2F3C

sub_3274

sub_33C6

sub_3415

sub_350E

sub_3577

sub_35A5

sub_4080

sub_4085

sub_4094

sub_40A5

sub_40AC

sub_40BF

sub_40F4

Decompilation won’t be an option here, but we can still use the CFG and XREFS to get a better understanding of this program. To better collaborate with my teammates and track our progress throughout the challenge, I used a tool I write called binsync. Through this public repo, you can see what we changed and when in our decompilers.

At this point in reversing, we may be tempted to just jump into the entry point and go off, but a wise reverser once told me:

“Don’t start where the program starts. Start where the interesting things start!”

At first, this seems like a stupid quote, but I promise it has actual application. A generally good piece of advice for reversing any program is finding the code location of output you associate to a state and then finding beacons. Beacons are structures and patterns that you recognize from programming or reversing. Recently, they have been a hot topic in research of qualitative analysis of reverse engineering. In those papers, they have recently shown that a breadth-first-search RE process that is both quick and precise tends to be the most effective when reversing.

What does this all have to do with getting the password? Well, we know the state we don’t want.

We are looking for a single control flow point that changes access to strings based on some symbolic value. After rapid clicking through the entry function callees, we find only two places that compare a value and then take wildly different branches. When I say wild, I mean things involving loops, string construction, and what we assume is a library call to print. The interesting one is here:

loc_2FA3:

ldb 3,s

cmpb ##1

lbeq loc_30A5

ldb ##8

leax ,y

jsr sub_1A63

tstb

lbne loc_3185

It calls the function at location 0x1a63, checks if it’s 1, then branches to places with a series of calls, loops, and printouts if correct. If false, it’s a quick succession to what looks like an exit. The hunch here is that we’ve found some kind of state authenticator.

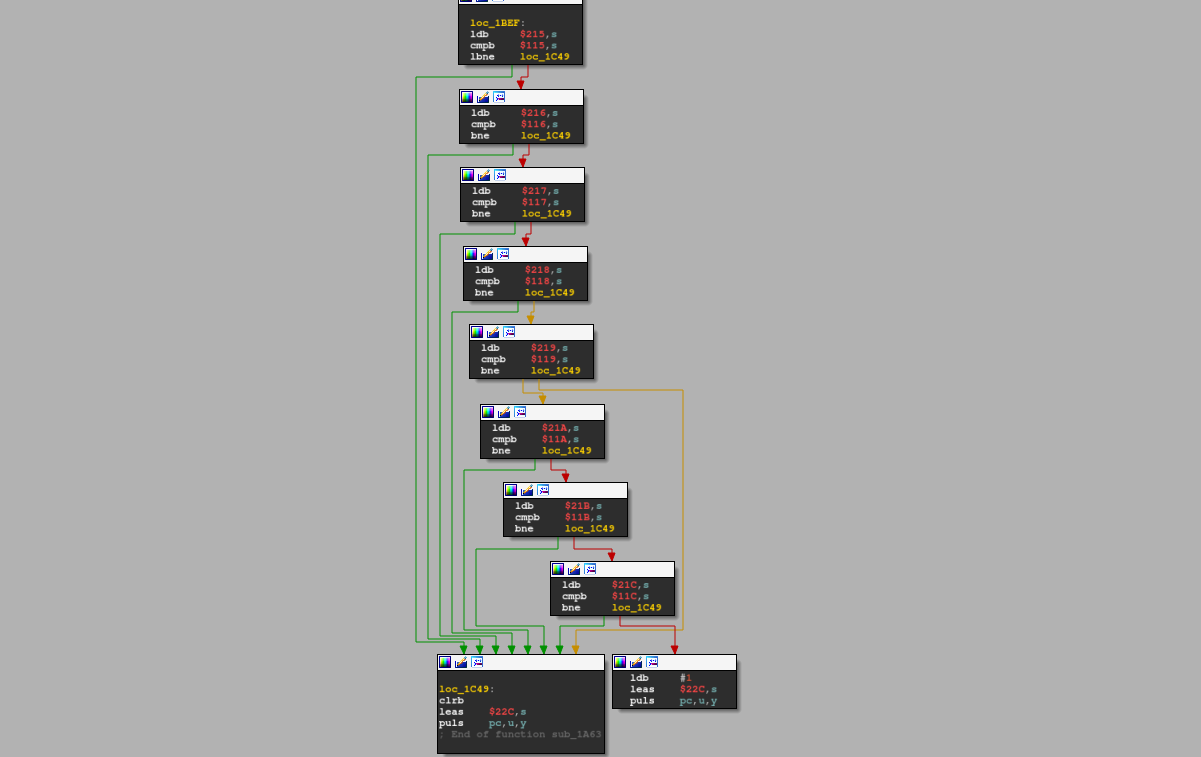

Recall our password is 8 bytes long. We look into the CFG of this function:

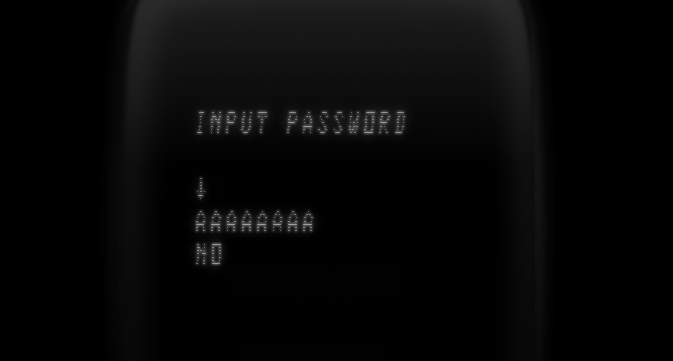

If that is hard to see, it looks like eight things are being compared. If one fails, the compare chain ends early and outputs 0. If it gets to the end, it outputs 1. Since we can see all the addresses being compared, we throw them in the debugger and confirm they are what we think they are. Dynamic analysis serves as a way for us to validate assumptions we made based on static analysis.

When we look in the debugger at the RAM offset of 116, we see our input AAAAAAAA has changed into something mangled. After seeing this, it’s safe to assume that the flag will also be mangled in the same way. Using this, we can now answer our reverser question of if all inputs affect the check. It really seems like it does not, but we can confirm that by running it through each char in the alphabet.

After two attempts, which get us a B, the first if-statement passes in the check tree. There are only eight chars, and each char only has 26 options… that is bruteforceable by hand! After 10 mins of guessing with a teammate, zammo, we guess all the chars of the key:

BLACKKEY

What does it mean? I have no idea.

A Recap of Techniques

We did the following:

- Find how normal people dev in this arch

- Use those tools to learn how the program starts and uses memory

- Use that knowledge to make tools work

- Question how authentications works

- Quickly search for patterns that match assumptions made in 4

I think the noteworthy takeaway from this section of the challenge was that most of the code you see is useless. This program is a game, so there will be an insane amount of code just for running the game and simulating things like game ticks. It was important that we found structures that looked familiar quickly and disregarded most other things.

The Real Game

After you get the password, you get to the second part of the game:

Instead of going in-depth into part two of this challenge, I again say go check out this blog if you are looking for a technical writeup of this section. I will instead give an overview of tricks we found useful for reversing both a game and an arch we did not fully understand.

In this second part of the game you are tasked with collecting coins (and completing an easter egg), then going to the flag at the end of the map. I find the game very hard to play, but zammo thought it was fun (he was also good, lol).

Tricks for Game Hacking

And now some tricks.

Make a fast workflow

In this game, if you fell off, you died and had to return to the password prompt, which was very painful. Instead of wasting time having to restart the game, finding ways to jump around execution points in the game and reverse actions are helpful. Because we are running in an emulator, we are blessed with the ability to “undo” instructions. In our workflow, we had:

- A quick

set $pccommand to get us back to the start of the game - A breakpoint set for the function called if you fall off

In the event of 2, we could undo the last few instructions to get back on the platform.

Observe Memory

Early in playing, we had a memory dump of the game on the screen. This showed us which values changed more than others. Through this, we were able to find our (x, y) coordinates storage location, our coin storage location, flags for winning or losing, and counter for jumps (suspicious). This technique of observing changes in memory, or differential memory analysis, is how many game-hacking tools like Cheat Engine work. Zammo found quite a bit of information like this.

Always observing memory gives you ample opportunity to see patterns in changes that may signify the existence of a variable (like health). In the case of this game, knowing a jump counter existed was crucial to finding the final flag.

Lookup Suspicious Constants and Patterns

I should’ve done this earlier in my reversing, but there was a strange pattern of 0-256 being set into an array and then shuffled. The program then used that value for xoring. I found it very weird. Once looking this up a little more, I found that this was just an inlined implementation of RC5. It’s important to remember our 4th reversing question: how are they hiding the flag string from us. In most cases, you can only hide a string through encryption. If the game has minimal memory and instructions, it’s likely the encryption will be:

- Fast

- Easy to implement

- Not take a lot of memory

In a perfect world, you would be able to recognize the most simple encryption algorithms in assembly. You can gain knowledge in this area by reading some survey papers on what encryption schemes are used most commonly used in this area of computing.

Generally, any time you see a large constant or a strange loop of setting many constants, do a quick google search for them. It’s likely a hashing or encryption algorithm.

Identify External Functions

Lastly, identifying external functions in games is probably the most important thing you can do when statically reversing big games. Usually, I like to start with finding which function is responsible for printing graphics to the screen. In this case, that information is what allowed us to find all prints (which is a small number) and find where the second flag is eventually decrypted and printed.

When you can, try to identify what looks like user-set memory access and library-set access. In embedded games like this, it will usually be made more obvious by access to ROM and RAM. On that note, if you don’t understand how memory is laid-out in your platform or game, you should get background knowledge on it from around the web.

Wrapup

I hope you enjoyed this quick overview of hacking around in another architecture. If you take anything away from this post, it’s that you often need to move fast when reversing and make a lot of assumptions that you confirm later (usually with dynamic analysis). You use these assumptions, plug background knowledge in the area, to identify beacons, and then go from there. See you next time \o.