Insomnihack22: Reversing a flawed ECC rng-as-a-service Go Server

TL;DR

Reversing a Go binary to find it generates flawed RNG from a P256 Elliptic Curve chosen with a reversible P and Q for number generation. Solution based on the Dual EC crypto paper.Introduction

During Insomni’hack teaser 2022, I worked on a reversing challenge called Nobus101 that ended up having a lot of fun use-cases for my debugging tool decomp2gef. You can all the challenge files and solve in shellphish/writeups

Collaborators

Challenge Description

The challenge is a single binary, nobus101.bin. The challenge description is:

An old Clyde Frog employee, J.S., gave us an access to a not so experimental PRNG:

curl http://nobus101.insomnihack.ch:13337

Scouting a Go Binary

You can often tell that a binary is a Go binary just by opening it in a decompiler and seeing the naming convention:

You will usually see something like main_*, which means it’s a function of the package main. You can also use a little hack:

strings -n 5 nobus101.bin | grep "goroutine"

Both work well.

Something I noticed instantly in this binary is the main_handleRequests function which is a tell-tale sign that the binary implements a Go built-in http server. This usually looks like:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

func hello(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "hello\n")

}

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/hello", hello)

http.ListenAndServe(":1337", nil)

}

So at this point, I assume it’s an RNG-as-a-service http-server.

One last thing to take note of before actually reversing this binary is trying to identify which functions are written by the user and which are just static linking of Go Libs. IDA actually does a pretty good job at telling the use which function is a user function and which is not in this case.

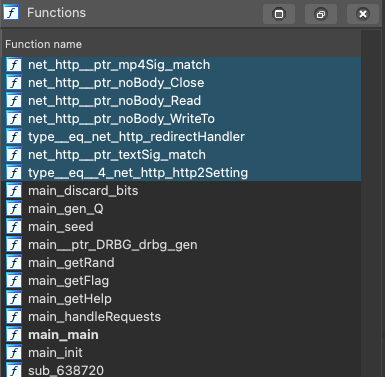

Usually, everything you see in main_ is a user-written function. You will also find other packages with some user-looking name, like: my_printer_. In this case, the binary is actually small. The entire program is contained within the main package. That means the functions are as follows:

main_discard_bits

main_gen_Q

main_seed

main__ptr_DRBG_drbg_gen

main_getRand

main_getFlag

main_getHelp

main_handleRequests

main_main

main_init

Understanding the HTTP Server

I was once told by a smart reverser to “never start at _start”, but in this case I think it’s really helpful to take a glance at the main_main of the binary which happens right after the init of main. It’s almost like an entry point.

There is a lot of trash in the decompilation because Go has a lot of Runtime checks. For the majority of these, you can ignore them. There is one easily distinguishable line in the decompilation:

os_OpenFile((__int64)"/tmp/nobus-logs", 15LL, 1089LL, 438);

This is opening a file. If at any point you need to search up what a function does, just take the string after the last _. In this case it would be OpenFile. Just search "Go OpenFile" to find exactly what the calling params are. In this case, it’s actually easier to just cat the file while the binary runs. So let’s run the binary:

./nobus101.bin

Since this is an http server, its expected that there would be no output in stdout, but it should have executed that OpenFile already, so we can check what’s in it:

└─ λ cat /tmp/nobus-logs

[NOBUS] 2022/02/07 13:32:22 init: seed:c1b129fd156bb3c3efa15b0b1c4146b8f44cc5310e18a4b8c36a2632a53cf3e2

[NOBUS] 2022/02/07 13:32:22 init: v1:d48545a2b590e3c340ff274216ce07211d735c4fc498d2508c9d6d5f0d56

[NOBUS] 2022/02/07 13:32:22 init: v2:bfeafd478ebf201d0a3812dd48839bfa175ea1174174723ee5da97f46ab2

[NOBUS] 2022/02/07 13:32:22 init: v3:ae5deca8f2368358a0b2ab1a60aee2dbd875d87d88d99fe74c37d6b060aa

These numbers look like random numbers and a seed, but we should confirm it. Let’s try connecting to the binary and see if we learn anything.

It’s unclear what this http server would be running on, so we can just guess that the description port is the same as this one:

└─ λ curl http://localhost:13337

NOBUS 101 - CTF Insomnihack 2022

--------------------------------

GET /prng - return two random values

POST /flag - submit the next value that will be generated by the PRNG and get the flag

Examples:

$ curl http://localhost:13337/prng

88bb6ab83d9f2ff423f37bd417923038d8a377916f7a62183e911407ff27

044630dbec4b71cb0a438c9f1c55e239a1d46b27b8583ae986e6e857e99b

$ curl -d "662e194be250f360dfce1c853caf2f4b27ad0b5b118f20ef927581df8e71" http://localhost:13337/flag

INS{XXX}

It is the same port. We actually get a lot of information here, mostly about the endpoints and how to win. We are looking to guess the next number in a random number sequence, which is a classic RNG break. Let’s confirm these nums:

└─ λ curl http://localhost:13337/prng

d48545a2b590e3c340ff274216ce07211d735c4fc498d2508c9d6d5f0d56

bfeafd478ebf201d0a3812dd48839bfa175ea1174174723ee5da97f46ab2

So the authors are nice and are logging the random numbers so we have a way to solve this locally in a debuggable way.

Let’s also just confirm that this only handling these two requests:

0x637EFA:

call net_http__ptr_ServeMux_Handle

nop

mov rax, cs:off_859650

mov [rsp+40h+var_40], rax

lea rax, aPrng ; "/prng"

mov [rsp+40h+var_38], rax

mov [rsp+40h+var_30], 5

lea rax, go_itab__ptr_http_HandlerFunc_comma__ptr_http_Handler

mov [rsp+40h+var_28], rax

lea rcx, off_6BDFC8

mov [rsp+40h+var_20], rcx

call net_http__ptr_ServeMux_Handle

nop

mov rax, cs:off_859650

mov [rsp+40h+var_40], rax

lea rax, aFlag_1 ; "/flag"

mov [rsp+40h+var_38], rax

mov [rsp+40h+var_30], 5

lea rax, go_itab__ptr_http_HandlerFunc_comma__ptr_http_Handler

mov [rsp+40h+var_28], rax

lea rax, off_6BDFB8

mov [rsp+40h+var_20], rax

call net_http__ptr_ServeMux_Handle

They essentially translate to:

func handleRequests() {

http.HandleFunc("/help", getHelp)

http.HandleFunc("/prng", getRand)

http.HandleFunc("/flag", getFlag)

http.ListenAndServe(":13337", nil)

}

Nice. Alright, enough overview of the http server. Let’s find out how the hell they are generating random numbers.

Random Number Generator

When looking at main_main again I took note of the user-made functions that were called:

main_seed()

main_gen_Q()

main__ptr_DRBG_drbg_gen(arg)

main__ptr_DRBG_drbg_gen(arg)

main__ptr_DRBG_drbg_gen(arg)

From what we know so far, and the output from the /tmp/nobus-logs, we can assume this:

1. make seed for RNG

2. ???? Q ????

3. make v1

4. make v2

5. make v3

Q is a strange thing to see here. It means the rng is related to a crypto system. Maybe RSA or Eliptic Curves (since you often use Q to represent a point on the curve).

At this point, I decided to look back at the main_init function which always gets called right before main_main once. You could use the init if you wanted to make sure something is usable across threads, like a global seed or value.

Looking at main_init, we see two interesting things:

crypto_elliptic_P256();

...

v9 = math_big__ptr_Int_SetString(

v4,

(__int64)"132867e88e82431dc40ba24e11bf3ec7ffb18764a3b4df1f5957fd5f37d8be40",

64LL,

16LL);

...

qword_864E88 = v9

...

So we are led to the what the Q means. It is related to Eliptic Curves, and it is a point on the curve.

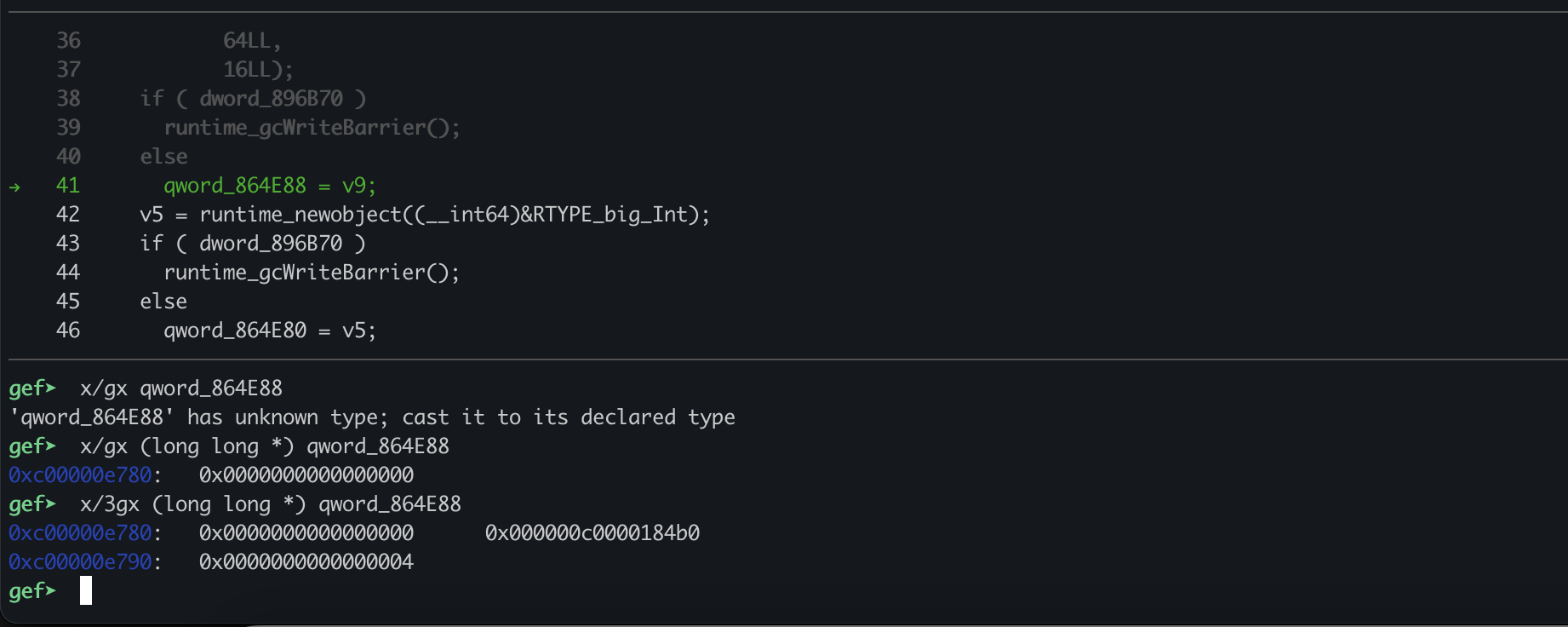

I was curious as to what the second big number was, because I thought it might be another important value so I checked it out. The assignment happens at 0x63856D, I decided to confirm this is a global in gdb. I connected with decomp2gef so I could examine the decompilation directly:

Take note of how the big_Int is stored in Go. The second qword is a pointer to the actual number

0xc00000e780: 0x0000000000000000 0x000000c0000184b0

0xc00000e790: 0x0000000000000004

If we examine it:

gef➤ x/4gx (long long *) ((long long *) qword_864E88)[1]

0xc0000184b0: 0x5957fd5f37d8be40 0xffb18764a3b4df1f

0xc0000184c0: 0xc40ba24e11bf3ec7 0x132867e88e82431d

It’s actually the same value we see set in the string 132867e88e82431dc40ba24e11bf3ec7ffb18764a3b4df1f5957fd5f37d8be40. This information is actually super useful to remember when trying to understand the varoious Big Ints we see set all over this program.

Understanding P256 EC

From searching around on the internet, it turns out that P256 is a well-known configuration of Eliptic Curves (ECs). At this point, I wanted to start understanding how this was utilized in Go. The docs provide a nice overview, but to really understand it, I took a look at the source.

func initP256() {

// See FIPS 186-3, section D.2.3

p256Params = &CurveParams{Name: "P-256"}

p256Params.P, _ = new(big.Int).SetString("115792089210356248762697446949407573530086143415290314195533631308867097853951", 10)

p256Params.N, _ = new(big.Int).SetString("115792089210356248762697446949407573529996955224135760342422259061068512044369", 10)

p256Params.B, _ = new(big.Int).SetString("5ac635d8aa3a93e7b3ebbd55769886bc651d06b0cc53b0f63bce3c3e27d2604b", 16)

p256Params.Gx, _ = new(big.Int).SetString("6b17d1f2e12c4247f8bce6e563a440f277037d812deb33a0f4a13945d898c296", 16)

p256Params.Gy, _ = new(big.Int).SetString("4fe342e2fe1a7f9b8ee7eb4a7c0f9e162bce33576b315ececbb6406837bf51f5", 16)

p256Params.BitSize = 256

p256RInverse, _ = new(big.Int).SetString("7fffffff00000001fffffffe8000000100000000ffffffff0000000180000000", 16)

// Arch-specific initialization, i.e. let a platform dynamically pick a P256 implementation

initP256Arch()

}

Every time I try to do a ECC challenge, I need to review the ECC Wikipedia for the equation for a curve:

y**2 = x**3 + ax + b

In addition, you have a base point of the graph, G, which acts as the generator. In this case:

G = (Gx, Gy)

As defined by the Go source (which is the correct way you use p256). You also have p (shown as P in Go since only private properties can be lowercase in Go), which is the field/module for this curve. It essentially bounds this curve by whatever it is, just like RSA’s N. Finally, n (shown N in source) is for computing the identity.

So what’s Q?:

Q = k*P

P and Q (not the P shown in source) are points on the curve and k is like the private key that turns P into Q, just like RSA. If this is interesting to you, I highly suggest checking out what CryptoHack has on this subject.

Where is the Bug?

So the author is using a crypto library in a well-known language that is implementing a well-known EC variant. Where could the bug be? I saw only two possible directions:

- The author is trying to show us some bug in Golang that can be exploited in the right scenario

- The author is trying to show us some bug when you choose a specific

Qandkwith P256.

I originally started with 1, but I pivoted to 2 after googling around a lot and finding a lot of forum discussion about people claiming P256 was backdoored. At first, I thought it was just nonsense, then I found this paper: Dual EC: A Standardized Back Door.

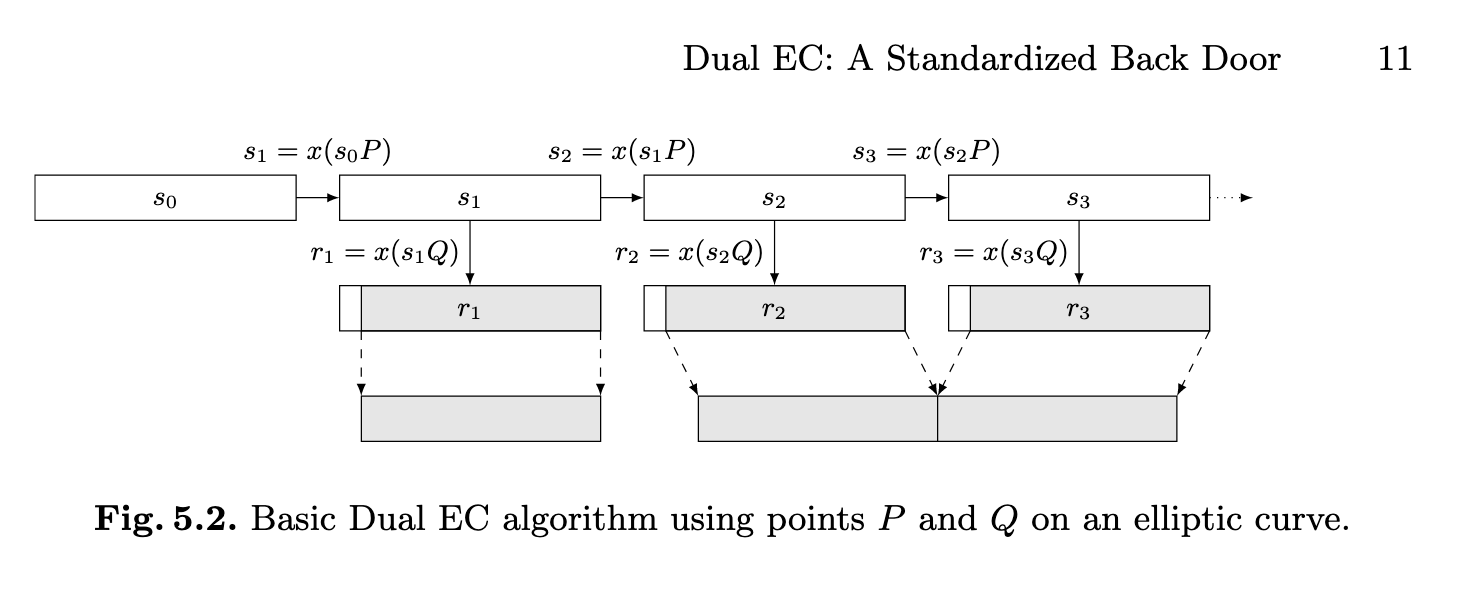

The Paper Spark Notes

The paper presents a way to, surprise surprise, guess the next random number in a series of given numbers when you know point P, Q, k and guesses before your current guess. They do this with some tricks on the choice of P and Q.

Lucky for me, I found a script of this exact attack implementation for UTCTF 2021.

So the question now becomes, what is P, k, and Q because we need them for the attack. Let the search begin.

Understanding Q Generation

The pinnacle of solving this challenge is understanding how Q is generated, which is of course done in the main_gen_Q:

void __golang main_gen_Q(__int64 a1, __int64 a2)

{

__int64 v2; // [rsp+8h] [rbp-70h]

__int64 v3; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-58h]

__int64 v4; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-50h]

unsigned __int64 v5; // [rsp+38h] [rbp-40h]

__int64 *v6; // [rsp+40h] [rbp-38h]

__int64 v7; // [rsp+48h] [rbp-30h]

__int64 v8[2]; // [rsp+50h] [rbp-28h] BYREF

__int128 v9; // [rsp+60h] [rbp-18h]

LOBYTE(v8[0]) = 0;

v8[1] = 0LL;

v9 = 0LL;

v6 = (__int64 *)qword_864E88;

v5 = 8LL * *(_QWORD *)(qword_864E88 + 16);

v7 = runtime_makeslice((__int64)&RTYPE_uint8, v5, v5);

if ( v5 < math_big_nat_bytes(v6[1], v6[2], v6[3], v7, v5, v5) )

runtime_panicSliceB();

(*(void (__golang **)(__int64))(a1 + 56))(a2);

if ( dword_896B70 )

{

runtime_gcWriteBarrier();

runtime_gcWriteBarrierCX();

}

else

{

qword_864E68 = v3;

qword_864E70 = v4;

}

v2 = (*(__int64 (__golang **)(__int64))(a1 + 48))(a2);

math_big__ptr_Int_ModInverse((__int64)v8, qword_864E88, *(_QWORD *)(v2 + 8));

}

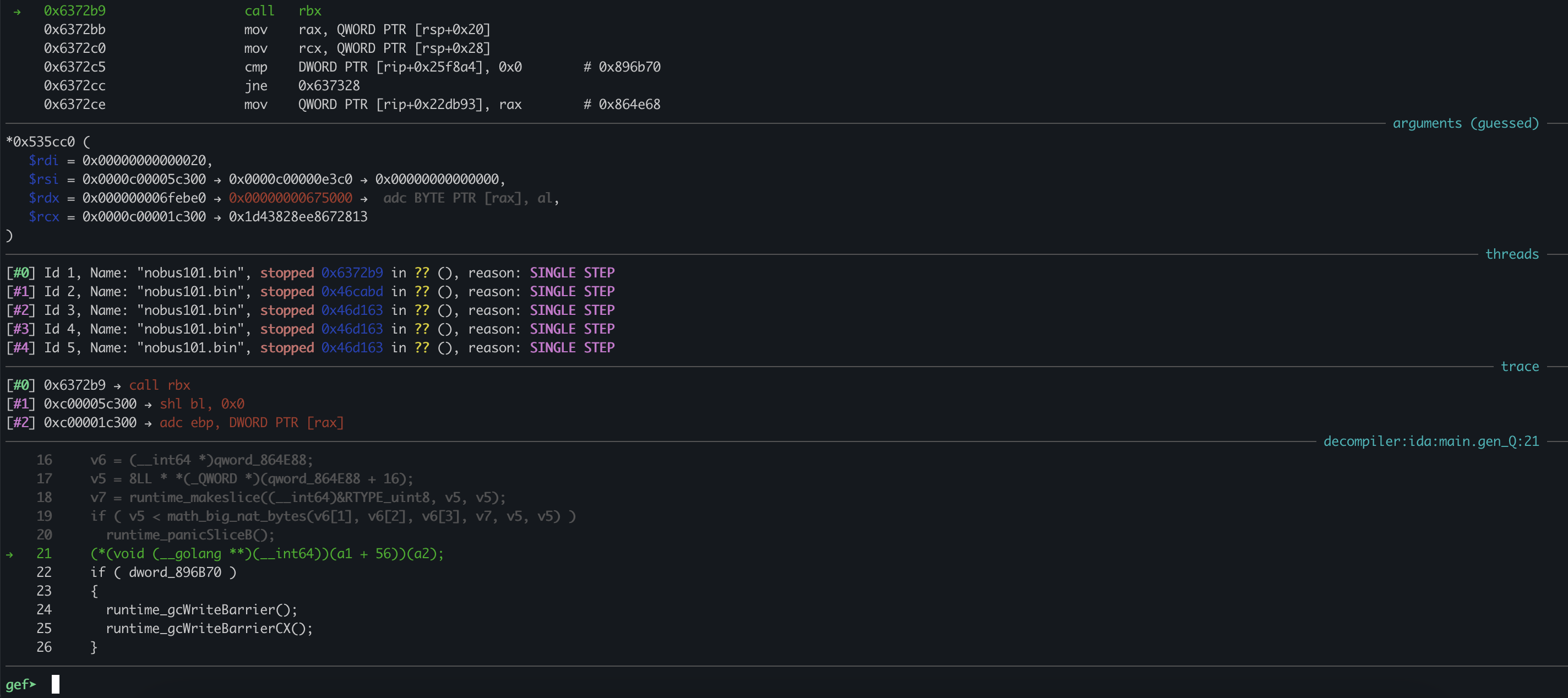

Lots of slicing into bytes to pass args, which is what makeslice does. The type is of uint8, which just means it’s a series of bytes. The real interesting part of this code is the function call happeing in the middle:

0x637282:

(*(void (__golang **)(__int64))(a1 + 56))(a2);

Where does it go? What is its actual args?

The address points to crypto/elliptic.p256Curve.ScalarBaseMult, which means we are preforming the multiplacation for Q = k*P we talked about earlier! The code we are calling corresponds:

func (p256Curve) ScalarBaseMult(scalar []byte) (x, y *big.Int) {

var scalarReversed [32]byte

p256GetScalar(&scalarReversed, scalar)

var x1, y1, z1 [p256Limbs]uint32

p256ScalarBaseMult(&x1, &y1, &z1, &scalarReversed)

return p256ToAffine(&x1, &y1, &z1)

}

To translate this Go a little, it’s important to remember that Go have types a function works on, as well as types for its args, and types for its output. A function depending on a type may sound confusing, but it’s just like using class methods. As an example, in Python you can do:

[].append(1337)

In a Go-like language, this would look like:

func (list) append(anytype x) (None) {

...

}

In assembly, this will look like having an extra pointer in the args, since IDA will think that the pointer the function is working on is a part of the function. So the function ScalarBaseMult really takes two args. The first arg is a p256 curve object. The second is the scalar k that we will multiply P by (whatever P is).

If the first arg really is a p256 object, then the first pointer in it should be a pointer to params which is a pointer to the constants we knew earlier. This is all based on the object being a Curve from Go.

(*(void (__golang **)(__int64))(a1 + 56))(a2);

gef➤ x/10x ((long *) $a2)[0]

0xc00005c300: 0x000000c00000e3c0 0x000000c00000e400

0xc00005c310: 0x000000c00000e440 0x000000c00000e480

0xc00005c320: 0x000000c00000e4c0 0x0000000000000100

0xc00005c330: 0x00000000006a743b 0x0000000000000005

0xc00005c340: 0x000000c00000e500 0x000000c00000e540

gef➤ x/10x ((long *) ((long *) $a2)[0])[0]

0xc00000e3c0: 0x0000000000000000 0x000000c0000181e0

0xc00000e3d0: 0x0000000000000004 0x0000000000000006

0xc00000e3e0: 0x00000000006b782d 0x000000000000004e

0xc00000e3f0: 0x000000000000004e 0xffffffffffffffff

0xc00000e400: 0x0000000000000000 0x000000c000018210

gef➤ x/8gx ((long *) ((long *) ((long *) $a2)[0])[0])[1]

0xc0000181e0: 0xffffffffffffffff 0x00000000ffffffff

0xc0000181f0: 0x0000000000000000 0xffffffff00000001

So a2 is a pointer to a series of pointers. And the first of those pointers points to a Big Int based on what we know of the structure of big ints. Then if we dereference the pointer that points to the value of the int, we see that its: 0xffffffff00000001000000000000000000000000ffffffffffffffffffffffff. That value may not look familiar at first, not until you convert the value the set to p (show P) in the Go source int to hex:

In [4]: p = 115792089210356248762697446949407573530086143415290314195533631308867097853951

In [5]: hex(p)

Out[5]: '0xffffffff00000001000000000000000000000000ffffffffffffffffffffffff'

Confirmed we are working with the direct pointer to our curve. Sweet, so we only have one more step to understand how Q is generated. Let’s look inside the ScalarBaseMult function we saw earlier. If we break in the middle of the function before the p256ScalarBaseMul happens we can examine what the scalar k is and what the P (the point) is they are basing it on… since we still don’t know that either.

0x535D98

crypto_elliptic__ptr_p256Point_p256BaseMult((__int64)v6, (__int64)v5, 4LL);

=======

7 __int128 result; // [rsp+F0h] [rbp+28h]

8

9 memset(v5, 0, sizeof(v5));

10 *(_QWORD *)&v5[0] = crypto_elliptic_p256GetScalar((__int64)v5, 4LL, 4LL, a2, a3, a4);

11 ((void (*)(void))loc_46BA51)();

→ 12 crypto_elliptic__ptr_p256Point_p256BaseMult((__int64)v6, (__int64)v5, 4LL);

13 *(_QWORD *)&result = crypto_elliptic__ptr_p256Point_p256PointToAffine((__int64)v6);

14 *((_QWORD *)&result + 1) = v4;

15 return result;

16 }

=======

gef➤ x/4gx ((long *) $v5)[0]

0xc000135de8: 0x5957fd5f37d8be40 0xffb18764a3b4df1f

0xc000135df8: 0xc40ba24e11bf3ec7 0x132867e88e82431d

gef➤

So it looks like the scalar k is 0x132867e88e82431dc40ba24e11bf3ec7ffb18764a3b4df1f5957fd5f37d8be40. I had a lot of trouble figuring out what v6 was since the pointers ran very deep, but it actually ended up being a pointer to two points inside the p256 curve pointer. I still did not understand what P (the point) was. I

Using the same method as above for the second call, PointToAffine, I was able to get the (Qx, Qy) for Q:

Qx = 0xe4443e00380471a612d205fc270dd16dff008f4adc4f2ad2c32fed8e74f76033

Qy = 0x07275f38738e8496bc0ade55de646372df388f04cdf6a09cf80108e0d2878ce5

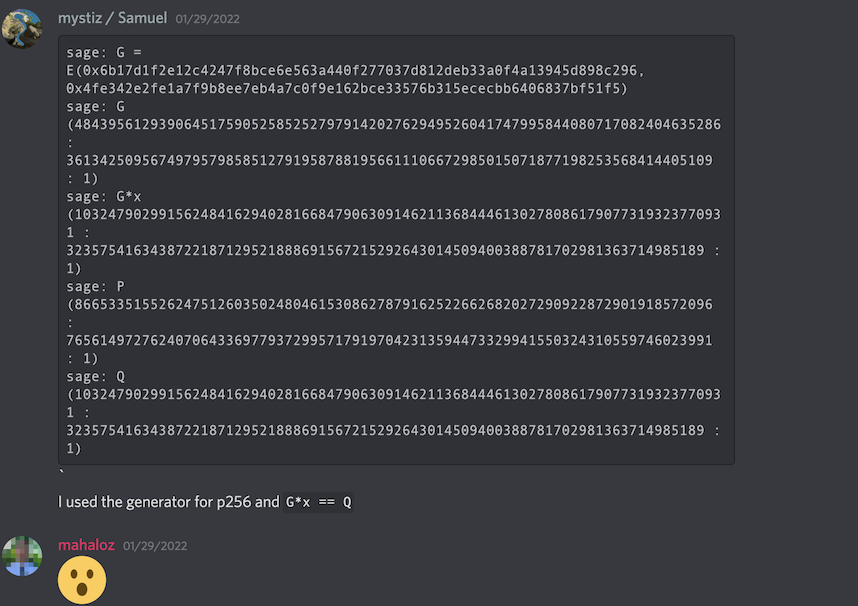

All I needed now was P, which I was not sure how I lost. I posted Q and k, and @Samuel mentioned earlier started messing with it. Then he noticed something while I was reversing:

So P (the point), is actually G, which we know from the standard description.

Breaking RNG

There is one other thing to note about how I knew this was the right attack. This is because in the paper it talks about the top 16 bits being lost when the original rng numbers are known. This aligns perfectly with the user-defined function main_discard_bits, which does the following:

int main_discard_bits(int a1) {

return a1 && ((2 ** 240) - 1);

}

Recall the numbers are 256 bits wide. Finally, we are ready to run the attack. We simply need to run the attack we found in the earlier paper and script while guessing the top 16 bits of both v1 and v2. We need to do this in less than 3 minutes to make it for the check on the server, so we make this process fork like crazy.

I used 32 workers to do this in around 10 seconds.

worker_id = 0

for i in range(5):

worker_id = (worker_id << 1) | (0 if os.fork() else 1)

if worker_id:

## do work

Thanks to help from @Samuel, this was the important part of the solving code:

## the numbers given by the server

v1 = 0x920324424eed2d0575b12b12857d9684ac3486b5087cddf8a60e4e129939

v2 = 0xce9c8866c6e5f6a0816d7c10dca0c2e6ffaa3101ccc882b371136766052

print(f"running", worker_id)

## optimized with np

arrs = np.array_split(list(range(2**16)), 32)

for dr in arrs[worker_id]:

_r1 = v1 + 2**240 * dr

try:

R1 = E.lift_x(_r1)

S1 = xi * R1

_s2 = Integer(S1.xy()[0])

_r2 = Integer((_s2 * Q).xy()[0])

_v2 = _r2 & ((1<<240) - 1)

if v2 != _v2: continue

_s3 = Integer((_s2 * G).xy()[0])

_r3 = Integer((_s3 * Q).xy()[0])

_v3 = _r3 & ((1<<240) - 1)

print(f'Got it!',hex(_v3))

Find the full solve here.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this challenge had a nice introduction to both Go reversing and to understanding a cool attack on RNG generated from the P256 EC implementation. As usual, this challenge was not possible to solve without both @redgate (whom stayed up late reversing with me) and @mystiz / Samuel.